itineraries

Discover Milan through the itinerary “Monumental Milan”, starting from:

This is the Monumental Milan, built in different periods and styles that have been programmatically and geographically sewn together. It’s the Milan that makes an impression. These monuments form the city image as described by Carlo Cattaneo, Giuseppe De Finetti and Aldo Rossi. It’s the stern, flawless Milan, so distinct from Rome, Turin and Venice. Largely a product of the 19th century, it was heavily restructured by Fascism, then bombed in the war, and finally rearranged by postwar reconstruction.

There are also significant traces of the Middle Ages in the Monumental Milan, albeit now isolated from the rest. Examples include the early Christian Basilica of San Lorenzo, the Romanesque Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio and the gothic Duomo. There are surprising Renaissance masterpieces, too, such as Bramante’s work in the churches of San Satiro and Santa Maria delle Grazie, or the Sforza Castle and Ospedale Maggiore by Filarete. Notable 19th-century architectures include Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, or rather the intricate network of galleries and arcades permeating several surrounding blocks. Milan’s unique collection of high-quality 20th-century architecture is also one of Europe’s finest: the Triennale and Palazzo dell’Arengario with their Fascist origins, the Vela by Moretti, Torre Velasca by BBPR, various works by Caccia Dominioni set in the urban fabric, Gardella’s Casa “al Parco” overlooking Parco Sempione, numerous works by Asnago and Vender, as well as Ponti, and the Milan Metro Line 1 by Albini, just to name a few from the 1950s and ’60s. Can all this be considered a museum of architecture?

Yes, but with one proviso: in Milan, since modernity is not regarded as iconic, neither is it treated as a museum piece. Milan’s modernity – whether of Fascist totalitarianism or relativist reconstruction – almost always merges into normality. The city is a patchwork of old and modern, with a street layout largely unaltered since medieval times. Many modern buildings are merely elements in a street-side curtain wall, blocks at the rear, interior restorations, added stories or redesigned facades, often verging on camouflage or invisibility. To a cursory glance, Milan’s modernity risks going unnoticed. Glass facades are a rarity, except along Corso Europa.

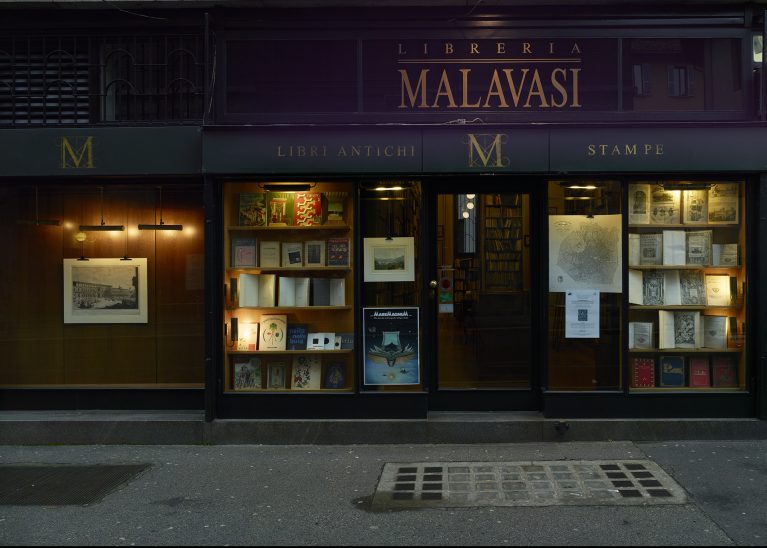

A stone’s throw from the Duomo, there are still large holes blown open by British RAF bombs in 1943. Today they’re mostly used as parking spaces, but sooner or later they ought to be repaired. Fashion, shopping, food and promenading are all part of Milan, and they perfectly fit the fragmented urban fabric at the heart of the city. Shops line the pavements, but they’re also in courtyards and on upper floors. Perhaps with a few detours, one finds a bit everything along the pedestrian stretch of about 1.5 kilometres connecting Piazza San Babila to Piazza Cairoli, passing via the Duomo and Piazza Cordusio: bookshops, stores, restaurants, churches and public buildings. It’s impossible not to mention the Hoepli and Malavasi bookstores. The latter has been selling antique and rare books since 1940, and today it is specialised in the field of antique books of the 16th-18th centuries. One of Milan’s main attractions is shopping, especially in the so-called Quadrilatero della moda, the fashion district delimited by Via Manzoni, Via Montenapoleone, Via della Spiga and Via Sant’Andrea. Every luxury brand can be found there. Prada settled in the area in 1913, when Miuccia’s grandfather Mario Prada opened the firm’s first store selling leather bags in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. A century later, the shop has been joined by Prada Galleria (photo below).

If you go for a stroll here, dive into the Milanese atmosphere of bygone times at Al Camparino, the historical bar opened by Davide Campari in 1915 in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. When it’s time for an aperitif, order a Negroni if you want something stronger (1 oz. Campari, 1 oz. Cinzano Rosso and 1 oz. Gin) or a Negroni Sbagliato (1 oz. Campari, 1 oz. Cinzano Rosso and 1 oz. spumante) if you fancy something lighter. Concerns have been voiced regarding two urban transformation projects along this itinerary – in Piazza del Liberty and Piazza Cordusio. Yet they are unlikely to change the somewhat prestigious architectural essence of these squares.

The charm of Milan’s city centre, as it appears today, lies in its capacity to endure the ups and downs of variable economic cycles practically unaltered, and in not falling prey to tourism. Four squares – Piazza del Duomo, Piazze della Scala, Piazza Cordusio and Piazza Cairoli – form a single grand urban monument that can be considered modern since it was conceived and constructed just 150 years ago. There is nothing comparable in Rome, Florence, Naples or Turin. Brera is a separate zone in the Centre district. With its cobblestone streets, cyclists bounce up and down off the pavements heedless of pedestrians. Brera also has a few special buildings. The historical HQ of the Corriere della Sera, for example, includes a sober insert designed by Vittorio Gregotti, one of the best interventions carried out in the centre in the last 20 years. The Habsburg Palazzo di Brera is also remarkable with its Pinacoteca art gallery, a cornerstone of Milanese identity (but Milan has plenty of beautiful palazzi, from Renaissance to baroque, neoclassical, 20th-century and vernacular). Near the entrance to the Pinacoteca one finds the Jamaica. In the 1960s this place was known as the “artists’ cafe”, and despite its years it still retains its charm. The Ca’ Brutta by Giovanni Muzio is another a must-see. Recently renovated, is now stands in all its eccentric and caricatured monumentality.